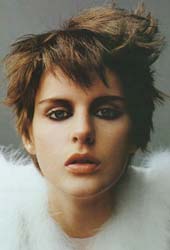

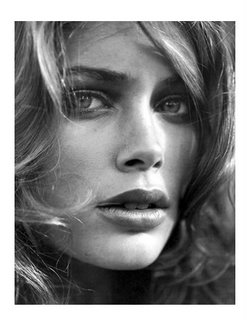

Ann Demeulemeester (2005)

[She burst onto the fashion pages to decades ago with designs that were called "deconstructionist." Today she is revered for clothes that respond to the intricacies of the body with quiet drama.]

JEFF: Belgium wasn't known for its fashion designers until the mid-'80s when you, Martin Margiela, and your other classmates from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp came along.

ANN: We started from zero, so nobody was expecting anything from us. But we were all very ambitious and had a kind of chemistry together. The only way to show the world that Belgium even had designers was to create something really good and different.

JEFF: As a student, were you looking at Comme des Garçons and agnès b.?

ANN: It was more like Mugler, Montana, and Versace. Punk had just started in London. Because Belgium is right in the middle of Europe, we felt its influence immediately.

I was so inspired by punk — it made me feel revolutionary and strong. That has stayed with me. The things that happen when you're seventeen or eighteen really shape you.

JEFF: How was that received by your teachers?

ANN: I wanted to revolt against school. I had a teacher at the Academy who loved classic Chanel. She tried to teach me how to make clothes like that. But I didn't want to make Chanel clothes, you know?

JEFF: Classicism implies a certain balance and order. Everything is proportional. Your work adds another dimension.

ANN: I want to cut nonchalance into my clothes. To do that, you have to work with balance. For example, a jacket pocket will hang differently after you've put things in it. Clothes will eventually take the shape of your body — a favorite coat will have a completely different soul than an identical jacket before it has been worn. The idea that garments are alive is a big inspiration. I want to fill them with soul. I've worked on that for a long time through the cut, the fabrics, and the treatments. I want to create the shape of your arm in the sleeve of the jacket.

JEFF: Did you develop this approach when you were in school?

ANN: No. You don't learn everything there. [laughs] At school, I had to learn technique and make historical costumes. But I happened to be part of a particularly ambitious class — why we were all there at the same moment, I'll never know.

We all worked like crazy, but we all ventured into very different directions. We fought a lot. If I loved punk, and another designer was into disco — that could cause a big fight.

JEFF: Was there a particular moment when who you are and what you do came together?

ANN: There hasn't been one exact moment when I thought, "This is my moment." Because I'm a hopeful person, I hope I can create many of those moments. Any time you have a great idea is a good moment. I'm very grateful for all the good moments I've had and for the people around me, the love in my life. But I never say, "Okay, I did it, it's fine." I'm always looking forward.

JEFF: I imagine that designing clothes for men is totally different than designing for women.

ANN: Yes and no. I follow the same rules, and I'm interested in the same look. But men's bodies are completely different. And women are used to being more playful with their clothes. It's okay for a woman to wear a man's suit and tie. But if a man came in here wearing a skirt and a fancy blouse, we would all laugh. As a woman, I can choose which side I express, but it's different for men. They are very straightforward with their clothes, which I appreciate.

JEFF: And what about their lives?

ANN: Men are not into a lot of role-playing. They just are who they are. Their attitude is, "Am I going to look confident today? Relaxed?" They know what they like to wear. Women search more. There are so many possibilities for us — it's more exciting, but it's also more difficult.

JEFF: You started your men's line in 1996. What was the impetus?

ANN: My husband and male friends were begging me. I said, "Okay, I'll do a small wardrobe." I didn't want to add another collection. But I showed it, and it sold — apparently there was a need that I could fill. I work with my husband's body in mind. I'm not in a girl's club. I always work with my husband.

JEFF: Is he a designer?

ANN: Originally he was a photographer. We were teenage sweethearts — we've been together since I was seventeen. Growing up together, we have everything in common. When I started out as a designer, he was working as a photographer. At a certain point we felt that if we both followed our own creative directions, it would separate us. As a creative person, he could have devoted himself to photography, painting, or design. But he said, "You need help, so I'll stop what I'm doing and help you. Then we can both concentrate on the same thing." He felt that as long as he could tell his story, he would be happy.

JEFF: So he has always given you feedback on your men's clothes?

ANN: Absolutely. It's very important because he and I have different criteria for judging them. I'll say, "This is beautiful," and he'll say, "I feel wrong in this." So we start again, until I arrive at an idea that feels right to him.

JEFF: You work a lot with textiles and fabric treatments. I saw some fabrics in your showroom with photographs of horses printed on them.

ANN: I've loved horses since I was a child. A few months ago, I was thinking about doing something with horses, but not the typical thing. I wanted to catch their beauty, the shiny strength of their skin. I knew I needed a photo that would capture that quality. So I started doing research, and I came upon Steven Klein's work. One of his photos had the shine, the muscles, and the veins that I was looking for.

JEFF: Kind of like your clothes.

ANN: Yeah. So I phoned him, told him my idea, and asked if I could use his photo. I told him, "Your picture expresses what I want to express." He sent me pictures, and I got to work. I printed this horse image on silk with an inkjet printer.

JEFF: Do you ever travel for inspiration?

ANN: I don't travel.

JEFF: So your clothes only draw on your life in Belgium?

ANN: No. I make clothes for the whole world! I sell a lot of clothes everywhere! [laughs] JEFF: Yes. But, your fans in Tahiti aren't going to wear your signature heavy leather boots.

ANN: Maybe not. But the fashion seasons are always off, anyway. The summer clothes come into the shops in January. I should put boots in my summer collection — people would buy them because they'd come out in the wintertime.

JEFF: Do you think that being Belgian has something to do with how honest and straightforward your clothes are?

ANN: Yes. There is something about our national character that is quite unpretentious. We're sincere, even humble. Maybe that's reflected in my clothes. I think a designer's background and culture are expressed in an uncontrolled way. I don't have a choice about it, it just comes out.

JEFF: Is there a particular type of person who wears your clothes?

ANN: I really follow my heart when I make a collection — I'm not designing for a type. People can mix and match and adjust the clothes to fit into their lives. I don't know exactly who will end up wearing my clothes. It's like creating a present for an anonymous person.

JEFF: Is that why you don't use logos?

ANN: I prefer meeting a real person instead of a label. The clothes can never be more important than the people themselves. They have to become part of them, part of their world.

JEFF: You love black and white. Do you ever have the urge to throw in a dash of, say, yellow?

ANN: Probably not. But never say never, eh? I ask a lot of questions when I'm designing. What do people want? What can I add that isn't there? I'm a very serious person. I don't want people to look ridiculous. I want them to be beautiful and human, not like dressed-up dogs.

JEFF: Actors work in ensembles and musicians usually play together. But writers work alone, holed up in their homes or offices. I have the feeling that being a designer is like being a writer — that it's very private.

ANN: In my case at least. I don't go to parties or lead a very glamorous life. I'm always working, studying, and searching. Sometimes I suffer by asking too much of myself. Designing is not an easy thing for me. I don't know how long I will go on doing this, because I can only do it very well or not at all.

JEFF: You've being doing it for a long time.

ANN: Yes, but I've never planned ahead. I just go from one season to the next. If I ever feel like I've told my story in this medium, it'll be time to move on to another.